Table of contents

FastAPI tutorial, the best Python framework?

FastAPI tutorial, the best Python framework?

These last few days I have been testing a Python library that is becoming famous, FastAPI, a framework for creating APIs, such as REST APIs or RPC APIs. FastAPI promises to help us create fast APIs in a simple way, with very little code and with extraordinary performance, to support high concurrency websites.

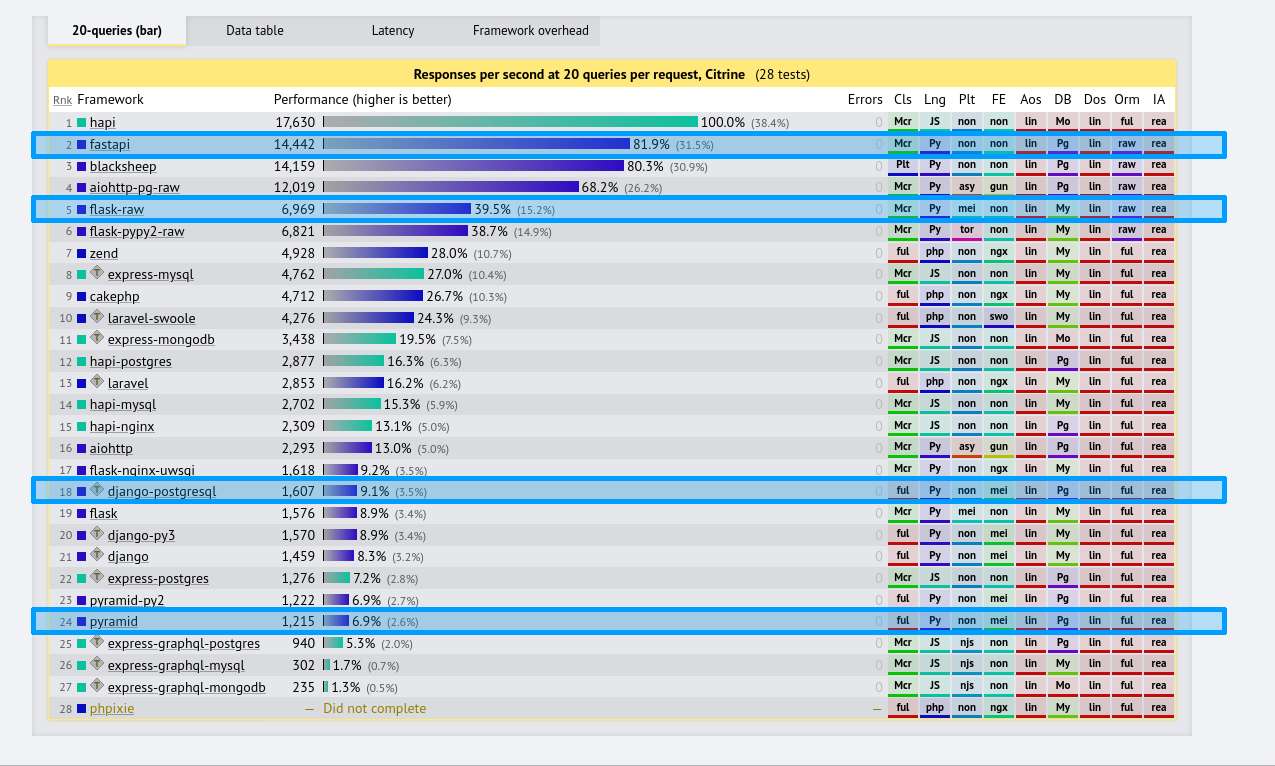

FastAPI vs Django vs Flask vs Pyramid

Is FastAPI really that fast? Yes, at least that’s the evidence. FastAPI is in first place in responses per second compared to more popular Frameworks such as Django, Pyramid or Flask. And it is also in the first places if we compare it with Frameworks of other programming languages, such as PHP or Javascript.

FastAPI vs Django

FastAPI focuses on creating APIs in a simple and very efficient way, Django can do the same using its DRF library and ORM, but I don’t consider them to be direct competitors. Why? Well, because Django focuses on being more of an end-to-end solution, covering everything from a sessions and authentication system , ORM, template rendering, form creation and management, middleware, caching system , its admin panel included , i18n and many other aspects.

On the other hand, FastAPI leaves the way open to the developer, so, as it covers different needs, the comparison does not apply.

FastAPI vs Flask

Unlike Django, I do consider Flask to be a more direct competitor to FastAPI. Both frameworks have some similarity in syntax and are characterized by being fairly lightweight and offering minimal functionality. FastAPI offers validation, while Flask does not, FastAPI offers automatic documentation, while Flask does not. In addition FastAPI offers better performance according to available tests.

See the following comparisons using information from Techempower . I have highlighted in blue the Python frameworks.

Performance for requests with a query

The number indicates the number of responses per second for a single query, of course the higher the better.

Performance for requests with 20 queries

But what about requests with higher loads? This image shows the number of responses for a request with 20 queries, again, the higher the better.

According to information provided by Techempower, FastAPI is tremendously faster than Django, Flask and Pyramid.

But how about its compatibility with newer versions of Python?

Typing and asynchronism in Python

FastAPI is fully compatible with the typing and asynchronism of the latest versions of Python.

In order to keep this tutorial as simple as possible I will use them only where necessary, if it is not strictly necessary to include them I will omit them. I mention the above so that you take into account that each code fragment where FastAPI is used can incorporate asynchronism and typing, as you consider necessary.

Now that you’ve seen why it’s worth using, why not give it a try?

FastAPI Basic Tutorial

FastAPI installation

To install it we are going to create a virtual environment with Pipenv, a virtual environment management tool . In addition to FastAPI we will need uvicorn; an ASGI server, which we will use to serve our API.

pip install fastapi uvicorn

Next we are going to create a file called main.py, here will be all the code that we will use to create our API.

touch main.py

And now we are going to place the minimum code to have a server.

# main.py

from fastapi import FastAPI

app = FastAPI()

@app.get("/")

def read_root():

return {"Hello": "World"}

First we will import the library, then we will create an instance of FastAPI. Then we will write a function that returns a dictionary and we will use a decorator with the path that we want our application to capture. That’s all.

Uvicorn will take care of serving the API we have just created by means of the following command:

uvicorn main:app --reload

Let us briefly analyze what we have just executed:

- main refers to the name of our file

- _ app is the FastAPI instance we create

- _ –reload tells uvicorn to listen for code changes

INFO: Uvicorn running on http://127.0.0.1:8000 (Press CTRL+C to quit)

As you can see, if everything went well, we will have a server running localhost:8000

curl localhost:8000

{"Hello":"World"}

And, if we make a request to port 8000, we will get our response in JSON format, without having to convert it from the Python dictionary.

Capturing parameters

Now let’s move from static routes to parameterized routes.

To capture parameters we will add these lines to the main.py file we already have. We import the Optional typing with the intention of capturing our optional parameters. For this example I’m going to use the typing provided by the newer versions of Python, note how we set item_id: int to accept only integer type values.

from fastapi import FastAPI

from typing import Optional

app = FastAPI()

@app.get("/")

def read_root():

return {"Hello": "World"}

@app.get("/items/{item_id}")

def read_item(item_id: int, q: Optional[str] = None):

# otra_funcion_para_item_id(item_id)

# otra_function_para_q(q)

return {"item_id": item_id, "q": q}

Inside the decorator we place between square brackets the name of the variable we want to capture. This variable will be passed as a parameter to our function

As a second, optional parameter, we will expect a GET parameter, named “q”.

In this case, the only thing our function will do is to return both values in JSON format. Although, you probably already realized that, instead of simply returning them, you can use that data to search a database, enter that information as parameters to another function and return something else entirely.

curl localhost:8000/items/42

{"item_id":42,"q":null}

Since we did not specify an optional GET parameter it returns a null instead. See what happens if we try to send an invalid value, i.e. not an integer.

curl localhost:8000/items/texto -i

HTTP/1.1 422 Unprocessable Entity

date: Sun, 11 Oct 2020 00:13:38 GMT

server: uvicorn

content-length: 104

content-type: application/json

{"detail":[{"loc":["path","item_id"],"msg":"value is not a valid integer","type":"type_error.integer"}]}

FastAPI takes care of letting us know that the value sent is invalid by means of an HTTP 422 response. Now let’s make a request that includes correct values for both parameters of our read_item() function.

curl localhost:8000/items/42?q=larespuesta

{"item_id":42,"q":"larespuesta"}

Notice how it returns the number we pass it, whatever it is, as well as our optional GET parameter called “q”.

REST

FastAPI handles HTTP methods in a fairly intuitive way, simply by changing the function of our decorator to its respective HTTP request method

@app.get()

@app.post()

@app.put()

@app.delete()

In addition it is possible to specify an optional response code as a parameter in each of these routes.

@app.post(status_code=201)

To corroborate this, let’s create another function, this one instead of using the decorator @app.get, will use @app.post and will return a code 201.

from fastapi import FastAPI

from typing import Optional

app = FastAPI()

# {...código anterior}

@app.post("/items/", status_code=201)

def post_item():

return {"item": "our_item"}

This decorator will capture any POST request to the url /items/. See what happens if we try to make a GET request, instead of a POST.

curl localhost:8000/items/ -i

HTTP/1.1 405 Method Not Allowed

date: Sun, 11 Oct 2020 00:56:06 GMT

server: uvicorn

content-length: 31

content-type: application/json

{"detail":"Method Not Allowed"}

That’s right, any other unsupported method will receive a 405 (Method not allowed) response. Now let’s make the correct request, with POST.

curl -X POST localhost:8000/items/

HTTP/1.1 201 Created

date: Sun, 11 Oct 2020 00:57:05 GMT

server: uvicorn

content-length: 19

content-type: application/json

{"item":"our_item"}

Notice that we receive a 201 code as a response, as well as our response in JSON format.

Cookies

Reading cookies

If we want to read cookies using FastAPI we will have to import Cookie and then define a parameter, which will be an instance of that Cookie. If all goes well we will be able to send a Cookie and FastAPI will return its value.

from fastapi import Cookie, FastAPI

from typing import Optional

app = FastAPI()

# {...código anterior}

@app.get("/cookie/")

def read_cookie(my_cookie = Cookie(None)):

return {"my_cookie": my_cookie}

Let’s use curl to send a cookie and have it processed by our view.

curl --cookie "my_cookie=home_made" localhost:8000/cookie/ -i

{"my_cookie":"home_made"}

Place cookies

To set cookies we need to access the response object of our HTTP request, and we also need to specify the typing of this parameter. Please remember to import it

from fastapi import Cookie, FastAPI, Response

from typing import Optional

app = FastAPI()

# {...código anterior}

@app.get("/setcookie/")

def set_cookie(response: Response):

response.set_cookie(key="myCookie",

value="myValue")

return {"message": "The delicious cookie has been set"}

See the set-cookie header in our response. The presence of this HTTP header indicates that we have received the instruction to set our cookie correctly.

curl localhost:8000/setcookie/ -i

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

date: Mon, 19 Oct 2020 20:45:08 GMT

server: uvicorn

content-length: 31

content-type: application/json

set-cookie: myCookie=myValue; Path=/; SameSite=lax

{"message":"Delicious cookies"}

Headers or HTTP headers

Read HTTP headers

HTTP headers are read in the same way as cookies. Please remember to import Header.

from fastapi import Cookie, Header, Response, FastAPI

from typing import Optional

app = FastAPI()

# {...código anterior}

@app.get("/headers/")

def return_header(user_agent = Header(None)):

return {"User-Agent": user_agent}

Ready, now we will have a header that will return the current User-Agent, with which we are making the request, which automatically sends curl with each request, so we should be able to capture it.

curl localhost:8000/headers/ -i

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

date: Mon, 19 Oct 2020 19:33:45 GMT

server: uvicorn

content-length: 28

content-type: application/json

{"User-Agent":"curl/7.52.1"}

In this case, as we made the request with curl, it will return the string “curl/our_version”. If we made the request with a web browser we would get the User-Agent value for that browser.

Placing HTTP headers

To place headers we need to access the response object, this object has a property called headers to which we can add values as if it were a dictionary.

from fastapi import Cookie, Header, Response, FastAPI

from typing import Optional

app = FastAPI()

# {...código anterior}

@app.get("/setheader/")

def set_header(response: Response):

response.headers["response_header"] = "my_header"

return {"message": "header set"}

Now we make a request to the url we just created. We expect the response to contain an HTTP header called response_header.

curl localhost:8000/setheader/ -i

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

date: Sat, 24 Oct 2020 16:11:31 GMT

server: uvicorn

content-length: 24

content-type: application/json

response_header: my_header

x-my_data: X-my_data

{"message":"header set"}

Middleware

Yes, although FastAPI is quite simple it also incorporates the functionality of using middleware as part of its request-response cycle.

Don’t you know what middleware is? Simplistically, a middleware is a piece of code that you place before the request, to “intercept” it and do (or not) something with it. A middleware works in a similar way to those relay races where the request and the response would be the stakes that are passed from one middleware to the other, each middleware can modify the request or the response or leave it intact to pass it to the next middleware.

Super simplified scheme of a middleware in the web context

To use middleware, simply place an @app.middleware(‘http’) decorator on a function. This function receives the web request object and a function called call_next, which will receive the web request and return a response.

from fastapi import Cookie, Header, Response, FastAPI

from typing import Optional

app = FastAPI()

@app.middleware("http")

async def add_something_to_response_headers(request, call_next):

response = await call_next(request)

# Ahora ya tenemos la respuesta que podemos modificar o procesar como querramos

response.headers["X-my_data"] = "x-my_data"

return response

The response to our request is obtained after calling call_next by passing the request object as parameter, so all modifications to the request go before the call to call_next, while all modifications to the response go after call_next.

from fastapi import Cookie, Header, Response, FastAPI

from typing import Optional

app = FastAPI()

# {...código anterior}

@app.middleware("http")

async def my_middleware(request, call_next):

# modificaciones a REQUEST

response = await call_next(request)

# modificaciones a RESPONSE

return response

Now let’s do a curl to localhost:8000 to see if it worked. See how we now have an HTTP header in the response, and it corresponds to the information we just put in.

curl localhost:8000 -i

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

date: Mon, 19 Oct 2020 19:20:35 GMT

server: uvicorn

content-length: 17

content-type: application/json

x-my_data: X-my_data

{"Hello":"World"}

As long as the middleware we created remains active, each new response we get will contain that header and its respective value.

Middleware included

FastAPI comes with a number of middleware included that we can use and add to the list of middleware through which our requests will pass. To add a middleware just use the add_middleware() method of our app.

You do not need to add the following code. It is just to let you know some of the options fastAPI includes as part of its code.

from fastapi import Cookie, Header, Response, FastAPI

from typing import Optional

from fastapi.middleware.gzip import GZipMiddleware

# from fastapi.middleware.trustedhost import TrustedHostMiddleware

# from fastapi.middleware.httpsredirect import HTTPSRedirectMiddleware

app = FastAPI()

app.add_middleware(GZipMiddleware, minimum_size=1000)

- GZipMiddleware: takes care of using gzip compression in your responses.

- TrustedHostMiddleware: with this middleware we can tell fastAPI which domains are safe, similar to Django’s ALLOWED_HOSTS variable.

- HttpsRedirectMiddleware: it is in charge of redirecting http requests to their https version.

Forms management

The first thing we have to do to handle forms is to install the python-multipart dependency to our virtual environment. You can use pip or pipenv, I will use pipenv.

Make sure you are within the virtual environment in which you are working.

pip install python-multipart

Once our package is installed, we will create a function that receives a parameter equal to the Form object. Remember, again, to import Form from fastapi.

Also note that if you want to add more fields just set more parameters for the function.

Yes, it may sound rather obvious but it is better to mention it.

from fastapi import Cookie, Header, Response, FastAPI, Form

from typing import Optional

app = FastAPI()

# {...código anterior}

@app.post("/subscribe/")

async def subscribe(email=Form(...)):

return {"email": email}

Now let’s try to send a data using a form using curl.

curl -X POST -F '[email protected]' localhost:8000/subscribe/

{"email":"[email protected]"}

We will see how it returns us a JSON object, with the mail that we sent in the form, as response.

File management

In the same way as for forms, file handling requires the python-multipart library. Install it using pip or pipenv if you haven’t already done so. Once this is done add File and UploadFile to the imports.

Please note how it is necessary to use Python typing for this example, if you don’t it will return an error.

from fastapi import Cookie, Header, Response, FastAPI, Form, File, UploadFile

from typing import Optional

app = FastAPI()

# {...código anterior}

@app.post("/files/")

async def create_file(file: bytes = File(...)):

return {"file_size": len(file)}

@app.post("/uploadfile/")

async def create_upload_file(file: UploadFile = File(...)):

return {"filename": file.filename}

For this example we will create a simple text file.

The following command will create a txt extension file in our current folder. If you are not comfortable using the GNU/Linux terminal visit my series of posts where I explain the basic GNU/Linux commands

printf "texto" > archivo.txt

Notice how a request to /files/ returns the size of our file.

curl -F "[email protected]" localhost:8000/files/

{"file_size":5}

While a request to /uploadfile/ returns us the name of our file

curl -F "[email protected]" localhost:8000/uploadfile/

{"filename":"archivo.txt"}

You have probably already noticed that in no case is the file being saved, but only made available to fastAPI, so that we can do with it whatever we want within our function.

Error handling

FastAPI has a number of exceptions that we can use to handle errors in our application.

For this example our function will only return an error, but you could very well place this exception on a failed search for an object in the database or some other situation you can think of.

from fastapi import Cookie, Header, Response, FastAPI, Form, File, UploadFile, HTTPException

from typing import Optional

app = FastAPI()

# {...código anterior}

@app.get("/error/")

def generate_error():

raise HTTPException(status_code=404, detail="Something was not found")

We choose the code to return with status_code and the additional information with detail.

If we make a web request to /error/ we will receive an HTTP 404 response, together with the response

curl localhost:8000/error/ -i

HTTP/1.1 404 Not Found

date: Mon, 19 Oct 2020 20:21:28 GMT

server: uvicorn

content-length: 36

content-type: application/json

x-my_data: X-my_data

{"detail":"Something was not found"}

If we wish we can also add HTTP headers to the response directly as an argument called headers in our exception.

from fastapi import Cookie, Header, Response, FastAPI, Form, File, UploadFile, HTTPException

from typing import Optional

app = FastAPI()

# {...código anterior}

@app.get("/error/")

def generate_error():

raise HTTPException(status_code=404,

detail="Something was not found",

headers={"X-Error": "Header Error"},)

Testing in FastAPI

FastAPI contains a client with which we can do testing. Before we start testing we are going to install the necessary packages to do it: pytest and requests.

If you want to go deeper in Python testing I have a post where I expose some of the Python libraries for testing

pip install requests pytest

Now that we have them we are going to create a test file called test_api.py and a init_.py_ file so that python can access our modules.

touch __init__.py test_apy.py

In our test_api.py file we will place the following code.

from fastapi.testclient import TestClient

from typing import Optional

from .main import app

client = TestClient(app)

def test_read_main():

response = client.get("/")

assert response.status_code == 200

assert response.json() == {"Hello": "World"}

As you can see in the code above:

- client.get() performs the request to root

- response.status_code contains the response code

- response.json() returns the body of the response in JSON format

If we run pytest we will see that the corresponding tests are executed to corroborate that each of the previous elements is equal to the expected value.

pytest

======== test session starts ===========

platform linux -- Python 3.7.2, pytest-6.1.1, py-1.9.0, pluggy-0.13.1

rootdir: /home/usuario/fastAPI

collected 1 item

test_api.py . [100%]

======== 1 passed in 0.17s =============

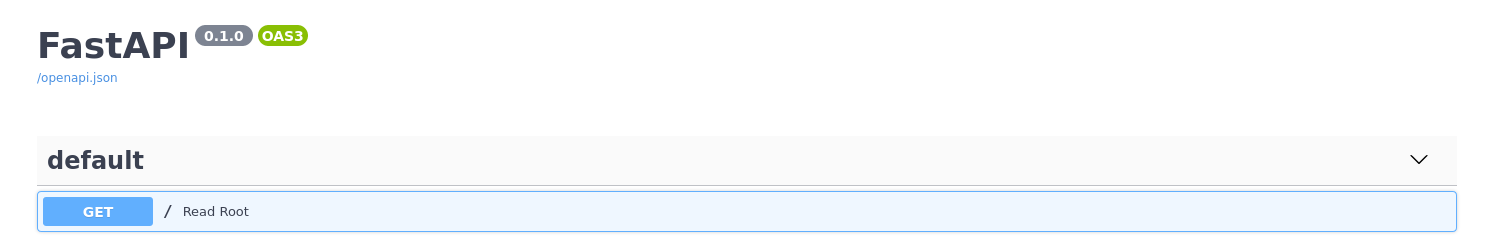

Documentation in FastAPI

Up to this point I have hidden one of the coolest features of FastAPI from you, please don’t hate me. That’s right, you know exactly what I mean: automatic documentation!

Yes, as you probably already knew, FastAPI has automatic documentation using swagger and redoc , you don’t have to add code, nor set a variable for this, just open your browser and go to your localhost:8000/docs/ and localhost:8000/redoc/ , respectively, and you will see the automatically generated interactive documentation.

Deployment without Docker

Deployment is also a simple task to perform.

To deploy without using Docker just run uvicorn, just like we did at the beginning of this tutorial.

uvicorn main:app --host 0.0.0.0 --port 80

Deployment with Docker

Deploying with Docker is super simple, the FastAPI creator already provides us with a custom Docker image that we can use as the basis for our Dockerfile. First let’s create a Dockerfile file.

touch Dockerfile

Now we are going to place the following inside:

FROM tiangolo/uvicorn-gunicorn-fastapi:python3.7

COPY . /app

We tell Docker to copy the entire contents of our current folder to the /app folder. After the Copy instruction you can add more code to customize your image.

Next we will compile the image.

docker build -t fastapi .

When it finishes compiling our image we are going to run a container in the background, on port 80. This container uses gunicorn to serve the content.

docker run -d --name fastapicontainer -p 80:80 fastapi

The configuration of uvicorn and the use of SSL certificates, either using Cerbot or Traefik or some other option is up to you.

This concludes my little FastAPI tutorial. This was only a small introduction with the options that I consider most relevant, please read the official documentation to go deeper into each of the options that FastAPI has available.