Table of contents

How to create a history of products with django and redis?

How to create a history of products with django and redis?

You are browsing an ecommerce site, a product catches your attention and you click to see it, but you are not convinced. You decide to see other options, click on a new product and, when you scroll to the bottom of the page, the page shows you the first product you saw under the caption “Recently viewed”. You can do the same with django and redis.

django and redis

Adding a section of visited products increases sales in an ecommerce and keeps the user longer on the page. It is normal to add this history to a user who is already in the database. The website managers have a history of the products we view, the ones we buy, how much time we spend viewing them and many other data but… what about the anonymous users who do not have a history? What about anonymous users who do not have an account?

History of a certain ecommerce site that no longer needs advertising.

Maybe you (or your company) are not interested in having stored in a database the history of millions of products visited by each anonymous user who visits the site, but you would still like to show each user, registered or not, the products he/she has seen.

Redis is a efficacious database engine, it works with volatile data, because it stores its information in memory, so its access is almost instantaneous, although volatile. However it is possible to dump its information to a permanent medium, such as mysql, postgres or another database, later. Surely we can use redis but… how are we going to differentiate one anonymous user from another?

There are many ways to address that problem, you can associate a user (and their history) with a cookie, ip or even an affiliate link, etc. The type of data you want to link depends on your business intentions. For this example we will use a session key from the session system that is already included in django by default.

Install redis on GNU/Linux

Before you can start using django and redis you must install the latter on your GNU/Linux operating system. If you have no idea about the basic commands in a linux environment I suggest you to visit my post that talks about the most common GNU Linux commands

sudo apt install redis-server

redis-server

Install redis for Python

Next we are going to install the package that links redis with Python.

pip install redis

In the settings.py file of our application, we add the default values we are going to use. These may be different if your redis server is in another location or if you chose another port instead of the default.

# settings.py

# ...

REDIS_HOST = 'localhost'

REDIS_PORT = 6379

REDIS_DB = 0

We will also ask django to save the session with each request and make sure that the middleware for sessions is active.

# settings.py

MIDDLEWARES = [

'django.contrib.sessions.middleware.SessionMiddleware',

# ...

]

# ...

SESSION_SAVE_EVERY_REQUEST = True

For this example I use a model called Product, but you can substitute it for the equivalent in your application.

# app/models.py

from django.db import models

class Product(models.Model):

# ...

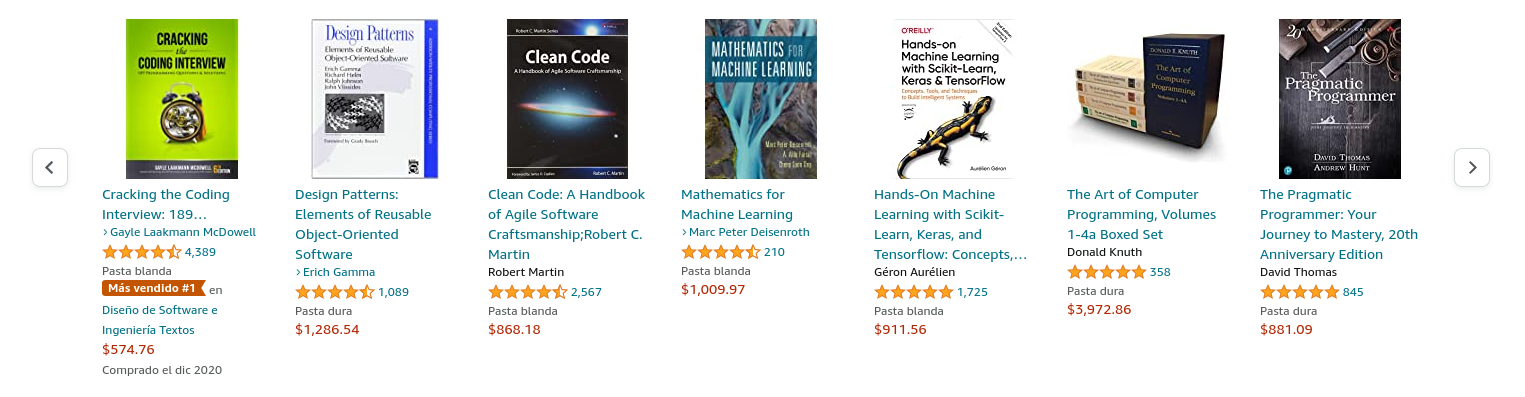

If you have come this far, but you have no idea how Django works, I have some posts where I review a couple of books that may help you: El libro definitivo de Django (Gratuito) or Django by example

Choosing the value to be used as a key in django and redis

First we must choose the time at which redis will save our access to the product. The view that returns the details of a product would be ideal. This way, every time a website user accesses the product details we will add the product information to their user id.

# app/views.py

from .models import Product

from django.shortcuts import get_object_or_404

def product_details(request, product_id):

products = Product.objects.all() # O el queryset que prefieras

product = get_object_or_404(products, product_id)

# ... más código

First, let’s get the object whose details we are querying, for that we use get_object_or_404, to which we pass a queryset or a model and the id to be searched.

Now we are going to create a series of functions to make our work easier, you can create them in a separate file, I will call it utils.py.

Connecting redis and python

In the utils.py file we are going to establish a connection between Python and Redis. The StrictRedis method will receive the values, these are the same ones we specified in our configuration file, so we can import them directly from there.

# app/utils.py

import redis

from django.conf import settings

r = redis.StrictRedis(host=settings.REDIS_HOST,

port=settings.REDIS_PORT,

db=settings.REDIS_DB)

Create a user identifier to be used as a key in redis

We want to associate each redis key to a user, so we need a function that returns a way to identify each user of our page. For anonymous users the ideal would be to use a session key, if we want to include users with a story we can associate them directly with their user.

Our function saves the session if there is no session_key, this way we will be sure to always have one. The function will return the session_key if the user is anonymous or the user if the user is already logged in.

For this it is necessary to receive the request object as an argument.

# app/utils.py

def get_user_id_for_redis(request):

if not request.session.session_key:

request.session.save()

return request.session.session_key if request.user.is_anonymous else request.user

Saving values in redis with lpush or rpush

The way in which it saves the data is by linking them with a key, that key has an associated list that will contain the information.

It is quite similar to a dictionary that has a list as its value. The equivalent in Python code would look something like this:

{"id_de_usuario_unico_1": [34, 22, 100, 5, 6], "id_de_usuario_unico_2": [112, 444, 3]}

The numbers we will store will be the ids or primary keys of the products.

To tell redis to extend that list at the beginning we will use lpush.

**The lpush method receives; the name of the key that we will store, as first argument; a value that it will add to the associated list of values at the beginning, as second argument. In addition lpush returns the size of the list associated to the key that we pass as first argument. The rpush method does the same but for the end.

Knowing this we will create a function that takes a user and a product id and pass them to redis to save them, our function will return the value returned by lpush.

# app/utils.py

def create_product_history_by_user(user_id, product_id):

product_history_length = r.lpush(user_id, product_id)

return product_history_length

Continuing the analogy above, lpush would do something similar to this.

{"id_de_usuario_unico_1": [34, 22, 100, 5, 6]}

r.lpush("id_de_usuario_unico_1", 1000)

{"id_de_usuario_unico_1": [1000, 34, 22, 100, 5, 6]}

Obtain a list of values associated to a key with lrange

Now that we have created a function to extend a list associated to a user, let’s create a function that returns that list.

Let’s use lrange

The lrange method allows us to pass a key (user_id) and will return the list assigned to it, from the initial value (0) to the end (4), counting from the beginning. That is, the elements with indexes from 0 to 4. As we do not want to repeat values, we will resort to a set comprehension to transform the values into integers.

# app/utils.py

def get_products_ids_by_user(user_id):

last_viewed_products_ids = r.lrange(user_id, 0, -1) # Devuelve [b'2', b'4', ...]

last_viewed_products_ids_list = {int(id) for id in last_viewed_products_ids}

return last_viewed_products_ids_list

This function will return only those redis values, so that we can know which products we will return from the database.

Creating a queryset from redis values

The above function returns a list of values, corresponding to id or primary keys of products in our database.

We will use that list of values to filter products in our database, a fairly common use of the django ORM that you should have no problems with.

Basically it means: get all the products and then filter them so that there are only those products whose id or primary key is in the list called product_ids.

# app/utils.py

from .models import Product

def get_product_history_queryset_by_user(product_ids, product_id):

last_viewed_products_queryset = Product.objects.all().filter(

id__in=product_ids).exclude(id=product_id)

return last_viewed_products_queryset

Note that you can replace the Product.objects.all() query with the queryset of your choice. You may prefer not to show all the products in your database, but only the active ones, the ones with inventory or any other combination.

Avoid storing repeated values

Since we don’t want the list of viewed products to repeat products, let’s make sure that the id or primary key of the product is not in the list we are getting before adding it.

To do this we just check that the product id is outside the list returned by the get_products_ids_by_user function we wrote earlier.

# app/views.py

from .models import Product

from django.shortcuts import get_object_or_404

def product_details(request, product_id):

# ...

user_id = get_user_id_for_redis(request)

product_ids = get_products_ids_by_user(user_id)

if int(product_id) not in product_ids:

create_product_history_by_user(user_id, product_id)

product_history_queryset = get_product_history_queryset_by_user(product_ids)

# ... más código

However now we run into another problem, what if our store has tens of thousands of products and our daily traffic is tens of thousands of users, do we really want to keep in memory such a large list of products visited? Most users won’t go through your last thousand products to see if they feel like buying something.

It is unnecessary to maintain such a long list if we are only going to access a few products.

How do we solve it? We need to create a function that helps us to keep the list of products associated to a key in redis in a limit.

rpop and lpop of redis remove an item from a list

The rpop method removes the last element of a list associated to a key and returns it The lpop method does the same, but with the first element

We can use rpop to remove the oldest element and purge the oldest elements. If with the last insertion the list grows beyond our limit (in this case 5) we will remove the oldest element.

# app/utils.py

from .models import Product

def limit_product_history_length(user_id, product_history_length):

if product_history_length > 5:

r.pop(user_id)

ltrim is an alternative to lpop and rpop

The function ltrim of redis is in charge of cutting the initial values of the list associated to a key, we indicate the initial index and its final index as arguments.

The difference with ltrim is that its execution time is O(n), since it depends on the number of elements to be removed, while for rpop it is O(1). If you have no idea what I’m talking about visit my post where I talk a bit about the Big O notation or stay with the idea that if we are only going to remove one element rpop is better. However you may want a different behavior and you may be better off using ltrim.

Redis has runtime information for each function in its documentation and can be very useful if the performance of your django application is important.

# app/utils.py

from .models import Product

def limit_product_history_length(user_id, product_history_length):

if product_history_length > 5:

r.ltrim(user_id, 0, 5)

Now we add the function to be executed only if there has been an insertion of an item in redis, i.e. if the current product is not in our list.

# app/views.py

from .models import Product

from django.shortcuts import get_object_or_404

def product_details(request, product_id):

# ...

user_id = get_user_id_for_redis(request)

product_ids = get_products_ids_by_user(user_id)

if product_id not in product_ids:

product_history_length = create_product_history_by_user(user_id, product_id)

limit_product_history_length(user_id, product_history_length)

product_history_queryset = get_product_history_queryset_by_user(request.user, product_ids)

# ... más código

Now that we have the queryset with the redis data, we can return it and render it in a django template, process it to return a JSON response or whatever your application requires.

# app/views.py

from django.shortcuts import get_object_or_404

from django.template.response import TemplateResponse

def product_details(request, product_id):

# ...

context = {"visited_products": visited_products}

return TemplateResponse(

request, 'product/details.html', context)

Assign an expiration date to data in redis

But what if we are not interested in how many products an anonymous customer sees, but how long we keep them.

Maybe today the customer wants to buy a particular product, but maybe we consider it useless to show him that same product three months later. Why not put an expiration date on the list we are saving? If the user does not revisit a new product after a certain amount of time has elapsed, the information will be deleted.

r.expire receives the key we want to expire and the time for its deletion, in that order, as its arguments. For this example I have assigned three months. And so the histories of inactive sessions that have been inactive for a long time will be deleted.

# app/utils.py

from .models import Product

def create_product_history_by_user(user_id, product_id):

product_history_length = r.lpush(user_id, product_id)

r.expire(user_id, 60*60*24*90)

return product_history_length

Redis has a lot to offer, and linking it with django will allow you to do a lot. I leave you the redis documentation in case you want to go deeper into it and its bindings in python.